Knatz family members fought on both sides of the war. Below is a picture of a photo postcard that shows the soldiers from Niedenstein in September 1914. Standing in the back row, second from the left is Johannes Knatz. Standing on the far left is Ludwig Knatz. Both soldiers survived WWI. Ludwig Knatz and his wife and daughter were killed in the allied bombing of the city of Kassel in WWII.

OUR WWI HERO- Sgt. Frederick A. Knatz WWI MEMORIAL TREE IN BROOKLYN

At 2 am on the morning of 15 July 1918, the start of the Second Battle of the Marne, one officer and 5 enlisted men, part of the observation detail of the advance infantry battalion, were captured by the Germans. One of the enlisted men captured was Sgt. Frederick G. Knatz, son of Jacob Knatz and Catherine Hill. Fred was born on 23 October 1896 in Manhattan. Although he was much older than my dad, Charles H. Knatz, Fred was my dad’s first cousin. At age 18, Fred enlisted in the Army at Ft. Slocum, New York, on 14 May 1915 as a private. Although his military records were destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, we can follow his military career through monthly muster rolls. As an Army private, he was part of General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico after Pancho Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico. He was elevated to Sgt. on 1 August 1917. He spent time at a training camp in Leon Springs, Texas. On 23 April 1918, he was shipped to France on the ship Tenadores from Hoboken, New Jersey, as part of Battery C of the 10th Field Artillery.

In less than four months, Fred was dead.

Around 6 am on the 15th, the officer from the captured observation detail made it back to camp. He had two bullets in his arm. He had been shot with his own gun in an attempt to escape. His assistant, Sgt. Knatz aided his escape. Knatz took a fatal bullet. On two occasions earlier that day, the officer provided information, informing the battalion of action in the field. At least one other captured man survived and was released from a German prison camp at the end of the war. He reported Knatz’s bravery to the New York Tribune on 9 March, 1919. This news article led me to investigate the availability of records for Frederick Knatz and his military unit. A week at the National Archives in Washington, DC, and Maryland this summer provided the opportunity to read the now-declassified records. Frederick was single when he died. However, his brother John named one of his sons Frederick G. Knatz. This Frederick would be my second cousin.

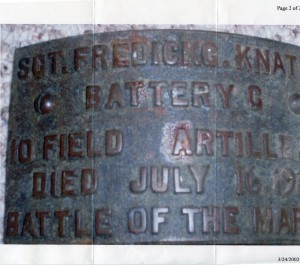

I connected with Frederick’s namesake in 2002 when someone in northern New Jersey recognized my sister-in-law Lisa’s last name, Knatz. Lisa put me in touch with this family in Demarest, New Jersey. This Frederick, born in 1921, was likely the “cousin Freddie” that my dad remembered because the WWI Fred died before my dad was born. This branch of the Knatz family retains the memorial plaque that the family attached to a tree in Brooklyn. (My Aunt Georgianna always said she had the “Tree that Grows in Brooklyn” after the same-named book, in her backyard, so there must be more than one tree in Brooklyn!)[2] These types of tree memorials were common when the bodies of lost soldiers were never recovered. Note the date of death on the plaque is 16 July, although all official records report his death on the 15th.

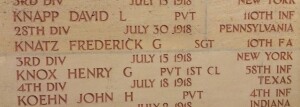

In September 2014, I was in Paris and visited the Aisne-Marne cemetery in Chateau-Thierry to see the Frederick G. Knatz memorial. I took a train from Paris to this small town. The train station had a phone you picked up to call for a taxi- none were available. The cemetery was only 10 kilometers away, so I decided to walk. The rail station manager thought that was too far and offered to drive me there. When we arrived, he noticed the cemetery was empty- not a living soul. Worried about leaving me there, he offered to pick me up in an hour. I happily accepted.

On the chapel wall, I found Frederick’s name. I had read online that if you walk up the hill behind the cemetery, trenches are still visible. I climbed the hill and saw rows of linear depressions. I found some wildflowers and brought them back to the Chapel to place on the floor in front of Frederick’s name. The second battle of the Marne was a turning point in World War I. It was the last German offensive and the beginning of the end for the German regime. The battle lasted from 15 July to 6 August. Our Frederick was lost on day 1.

Below is a picture of a curved plaque made to honor Frederick G. Knatz who was lost in the Battle of the Marne in 1918. The plaque was placed on a tree in front of the Knatz house in Brooklyn. If you look at the Walking Brooklyn website, you can see that using trees as memorials was something pretty common in WWI, although the Knatz memorial is the only one that I know that was curved and placed right on the tree. I imagine this was because families in WWI had nothing to bury. The plaque is now with the Fred Knatz family in northern New Jersey (Demarest). A temporary cemetery was established near Belleau Wood for the soldiers killed in this battle and in 1921 the US Congress authorized retention of this site as one of the eight WWI military cemeteries on foreign soil. Today is it known as the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery in Belleau. The cemetery contains the graves of 2290 American soldiers killed in the Battle of the Marne while the chapel contains the names of 1060 (the Tablets of the Missing) who are resting in unknown graves. Frederick was officially classified as missing in action. He name can be found on the tablets of the missing.

The inscription on the plaque that was on the tree in Brooklyn reads

SGT FREDICK G. KNATZ

BATTERY G

10 FIELD ARTILLERY

DIED JULY 16, 1918

BATTLE OF THE MARNE